09 July 2018

High-density planting and pruning case study

High-density planting and pruning case study:

Sunmar Orchards, Sunraysia

Key points

High-density plantings boost returns

Different layout, different management

Cashflow break even reached sooner

High-density plantings are delivering very good long-term returns to Sunmar Orchards in the Sunraysia region, the results of which are backed up by an economic analysis by the NSW Department of Primary Industries (NSW DPI).

Field view of a twin row young planting of navels at Sunmar Ochards.

Daniel Lazar manages 100 hectares of citrus at Sunmar Orchards owned by John Keams in the Sunraysia region. Maximising productivity and efficiency from established blocks with high-density plantings of Afourer mandarins and navel oranges is one of the business’s key targets.

At the NSW DPI citrus roadshow in October 2017, Daniel presented Sunmar’s high-density management growing techniques. This article captures his presentation.

Traditional versus high-density plantings

The traditional standard density of citrus tree plantings is about 440 trees per hectare (planted at 6.5m × 3.4m spacings). Sunmar Orchards has two types of high-density planting layouts; a twin row and a standard layout. The twin row high-density trees are planted at 952 trees/ha and the standard layout high-density trees are planted at 600 trees/ha (5.2m × 3.2m) (see Figure 1).

Daniel has been managing the orchard for two years and emphasises that the high-density plantings require an intensive annual pruning program. Without annual pruning the productivity of the high-density block can quickly decline below traditional planting densities.

As the trees grow, the row spacing closes, so the trees have to be hedged more frequently to allow for tractor access. For high-density trees with narrow row spacing (i.e. less than 5.5m), annual side hedging could be required. Hedging will cut off bearing wood and the potential crop. The solution is to implement an intensive annual hand pruning program that results in more fruit bearing inside the tree. The trees will still need regular hedging, perhaps every second year instead of annually and, when the trees are hedged, only a small portion of fruit-bearing shoots are cut off (see Figure 2).

The twin row layout does require a few extra herbicide sprays and a higher application coverage volume in the early years. Irrigation and foliar spray volumes also slightly increase. However, these extra costs are minimal in terms of the total cost of production.

FIGURE 1: The twin row planting layout (left) and the standard planting tree layout.

FIGURE 2: An unpruned or poorly pruned tree (left) has left most of the fruit on the outer parts of the canopy which is cut off (grey rectangle) when hedged. An intensively pruned tree (right) has a portion of fruit growing inside the tree that remains after hedging.

To enter the Chinese export program the blocks needed to be trunk band sprayed and this is impossible for the twin row layout blocks using a conventional trunk band sprayer that can only spray one side of the trunk per tractor pass.

Daniel overcame this problem by inventing a trunk band sprayer that can spray all around the trunk from a one-side tractor pass.

Hand pruning in high-density plantings

Daniel starts hand pruning trees when they are young so the trees have a good structure by maturity. Average annual pruning costs are $1.60 per tree on the standard high-density layout ($1000/ha) and about $1.30 for the twin row layout ($1250/ha). The twin row layout trees are smaller and therefore have a slightly lower per tree cost. Pruning costs will vary season to season.

The program has been producing very good long-term average yields of navels of about 55t/ha for the standard layout high-density navels and 63t/ha for the twin row layout. Without the annual hand pruning program, yields would be 15 to 20t/ha less; that’s a loss of up to $13,500/ha ($650/t fruit price). Investing $1250/ha in pruning and getting $13,500/ ha return is a very good investment. Daniel says he also gets less blemished fruit which increases his pack-out and per ton price.

The take home advice Daniel wishes to provide growers is high-density planting will provide higher early yields and twin row planting will provide higher mature tree yields, but annual hand pruning is essential to maintain good yields.

An economic analysis

NSW DPI has done an economic analysis of various high-density planting scenarios based on Sunmar Orchard’s experience. The scenarios were analysed using the 20-year NSW DPI citrus budget spreadsheets and based most assumptions on Sunmar’s information. Three scenarios were analysed:

1. Traditional single row layout at 440 trees/ha:

- 6.7m × 3.4m spacings

- Mature tree; year 12, canopy diameter 4.2m, tractor access 2.5m and canopy surface cover 63%

2. High-density single row layout at 600 trees/ha:

- 5.2m × 3.2m spacings

- Mature tree; year 10, canopy diameter 3.3m, tractor access 1.9m and canopy surface cover 63%

3. High-density twin row layout at 952 trees/ha:

- Mature tree; year 9, canopy diameter (two trees) 5.4m, tractor access 1.9m and canopy surface cover 74%

Note: tractor access is the space between trees along the row that enables machinery to pass through.

The economic analysis is limited to the assumptions chosen in the budget spreadsheets, which are available from NSW DPI on request.

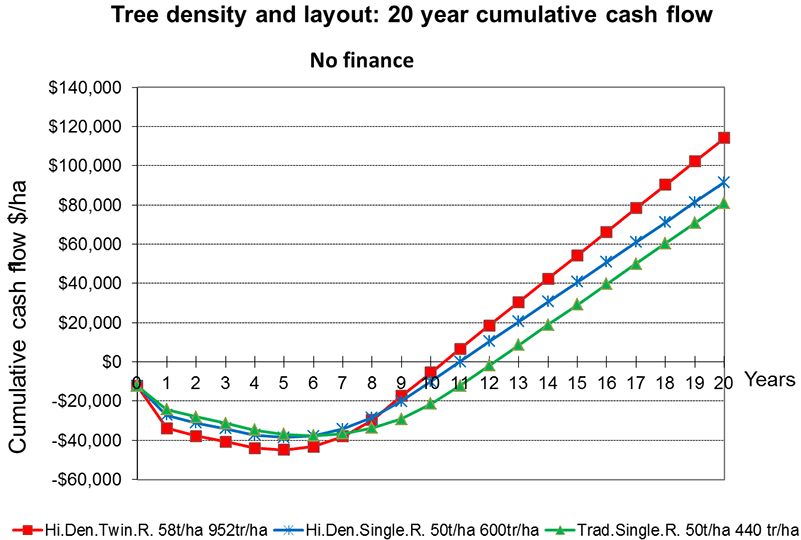

Figure 3 presents the results outlining the cumulative cash flow for each scenario over 20 years. During the first 11 to 13 years the enterprise is in debit since substantial cash was spent in buying trees and preparing the land for planting. Although yield might commence in year three, it takes numerous years of income to repay the land development and planting debit.

FIGURE 3: The cumulative cash flow of navel oranges at: high-density twin row layout (Hi.Den.Twin.R); high-density single row layout (Hi.Den.Single.R. 600 trees/ha); and traditional density single row layout (Trad.Single.R. 400 trees/ha).

The high-density plantings have the higher debit due to more trees planted per hectare, but they produce higher yields than traditional density planting in the early years and are able to pay off the debt quicker. This results in the cash flow breakeven point reached one to two years earlier for the high-density plantings (years 10 to 11) as compared to the traditional density planting (year 12).

The cumulative yield at year 20 indicates that the high-density twin row layout scenario has the highest cumulative cash flow followed by the high-density single row layout and last is the traditional layout (Table 1).

An important way to analyse long-term budgets is net present value (NPV). Because the cash flows in Table 1 represent a 20-year prediction, the buying power of $100 today is not the same in 20 years’ time, it will be less due to inflation and the option of putting the $100 in a bank and obtaining interest on it for 20 years. For example, if you put $100 in the bank at 5% interest for 20 years it would be $265. Thinking in reverse, $263 of income in 10 years’ time or $265 in 20 years’ time is actually worth $100 in today’s terms at a 5% discount rate (i.e. put $100 in the bank at 5% interest).

TABLE 1: Cumulative cash flow and net present value for year 20 for all scenarios (per ha)

The NPV over the 20-year period in all scenarios provides a positive result and the differences between each scenario are between about $10,000 and $20,000/ha.

It is a personal choice whether the differences in cash flow and NPV over 20 years are sufficient to justify the extra effort of planting and managing a high-density block. Budgets are very dependent upon their assumptions and some assumptions can significantly change results. For example, growing your own nursery trees can reduce the initial debt and favour high-density planting.

Management and cultural practice factors are also a very important consideration. The higher density trees require the extra effort of annual pruning, however the trees will be smaller than the traditional density trees and will be easier to harvest and spray. Picking labour favours smaller trees because they require less or no ladder work which makes them faster to pick and there are less ladder related injuries.

To help growers better assess their personal situation the Excel spreadsheets used to develop the high-density scenarios will be available in autumn 2018 at the NSW DPI citrus website for growers to customise pricing and management assumptions to their needs. Draft versions of the Excel spreadsheets are available from Steven Falivene (steven.falivene@nsw.dpi.gov.au) prior to autumn 2018.

MORE INFORMATION

This article was first published in Citrus Connect — NSW Department of Primary Industries’ e-newsletter for citrus growers. Citrus growers may subscribe to the newsletter at tinyurl.com/citrusconnect.

AUTHOR

Steven Falivene, NSW DPI, (03) 5019 8405, steven.falivene@dpi.nsw.gov.au

Membership

You are not logged in

If you are not already a member, please show your support and join Citrus Australia today. Collectively we can make big things happen.