21 February 2018

Preventing postharvest fungicide resistance

Preventing postharvest fungicide resistance

21-Feb-2018

By John Golding and John Archer

Key points

- Postharvest fungicide resistance occurs and is a problem

- Good shed hygiene can reduce the risk of resistance

- Don’t always use the same fungicide

Using postharvest fungicides is an important method of controlling the development of decay during handling and marketing. However, postharvest fungicides can sometimes fail to work due to the development of resistance by the decay fungi to the fungicide. Fungicide resistance is a serious and important postharvest problem which needs to be actively managed in the packing shed to minimise potential losses.

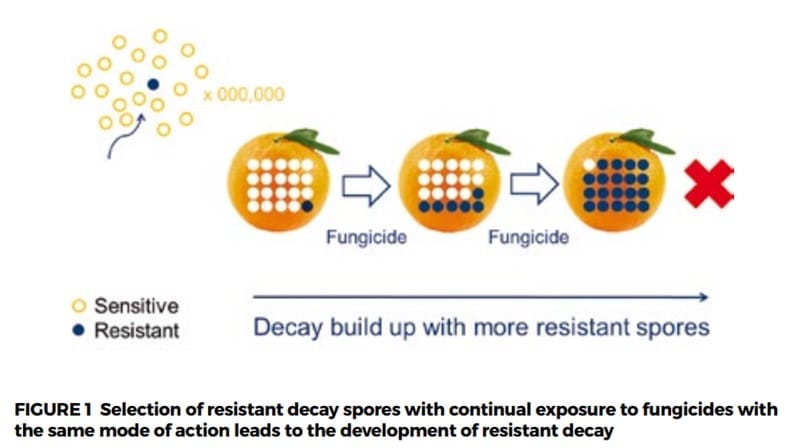

Fungicide resistance can occur in sheds and coolrooms which have poor hygiene and/or which practise ongoing use of the same postharvest fungicide. Resistance arises when a single decay fungi spore that is resistant to a fungicide multiplies. The continued selection of these resistant spores can happen when the same fungicide is used, and these spores can multiply, allowing full resistance to develop.

Survey to assess the presence of decay-causing fungi

Earlier this season the NSW Department of Primary Industries conducted a survey of packing shed hygiene and resistance to postharvest fungicides across Australia as part of the Hort Innovation Citrus Postharvest Program (CT15010).

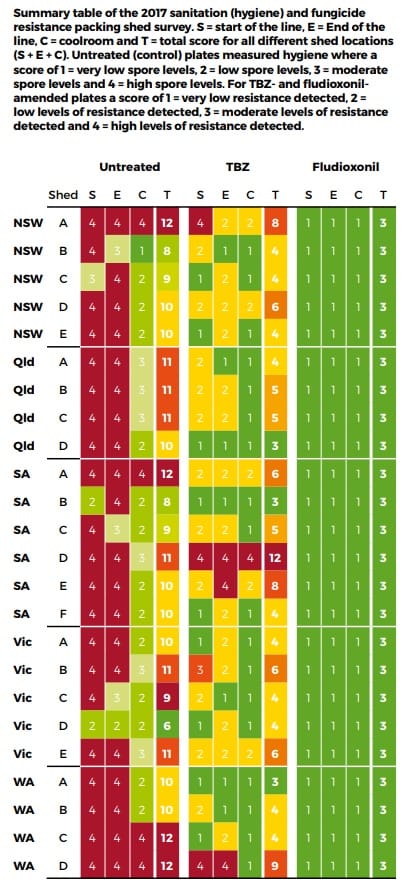

Agar petri dishes with different fungicides were exposed in sheds during the main packing season to estimate the levels of fungicide resistance present. The plates were put into the start of the packing line, the end of the packing line and the coolroom. In the major survey, the postharvest fungicides used were thiabendazole (TBZ) (Vorlon® or Tecto®) and fludioxonil (Scholar®), while in the later stages of the survey, imazalil (Magnate® or Fungaflor®) was added. If decay spores in the air of the packing shed landed on the plates treated with fungicide and then grew, it was shown that there was some technical resistance in that facility to that fungicide.

Shed-by-shed hygiene comparison

Results showed there were large differences between sheds. The plates placed inside Shed 1 had very few fungi spores, even on the untreated plates, which indicated this shed had good hygiene practices with very low numbers of decay-causing fungi. In addition, there was no evidence of any fungicide resistance, with no fungi having grown on the plates treated with fungicide. This was a very good result for this grower and demonstrated the positive effects of good sanitation and fungicide use.

In contrast, the results from Shed 2 showed relatively high levels of decay-causing fungi spores in the untreated plates, indicating relatively poor shed hygiene. In addition, some technical resistance to TBZ and imazalil fungicides was detected, particularly against TBZ. The detection of technical resistance was a concern and management of shed hygiene and resistance is required.

The results from the different packing sheds around Australia showed there was a high level of variability in the management of hygiene and levels of technical resistance between the different packing sheds. The majority of the survey was conducted with TBZ and fludioxonil.

The results showed very little evidence of resistance to fludioxonil as this fungicide was not widely used by industry. However, there were some sheds which had significant technical resistance to TBZ. The management to minimise fungicide resistance requires a whole-of-system approach, starting at harvest and extending through to packing and storage.

Reducing resistance

Optimise fruit health

Optimise fruit health

It is good postharvest practice to minimise physical damage to fruit during harvest and handling. Handle all fruit carefully, as most postharvest-decay fungi can infect only through wounds in the peel. Therefore, reducing injury will reduce the incidence of decay.

The Australian Citrus Harvest Handbook was released in 2017 and contains excellent guidelines on the correct harvesting and handling of citrus. In addition, limiting the storage of fruit and keeping fruit at optimal storage temperatures reduces ageing of the fruit and therefore its susceptibility to decay. These factors not only are good postharvest practices but also reduce the risk of fungicide resistance developing.

Use best hygiene practices

Good shed hygiene is crucial to minimising the risk of fungicide resistance. Lowering the population of decay-causing spores in the shed and coolroom and on the fruit is key to a successful management program. Having fewer fungi spores in the shed reduces the risk of resistance developing.

Steps to ensure this include regularly sanitising equipment, coolrooms and the packing line by washing down (or using fogging technology). It is absolutely critical that all culled and especially decaying fruit be removed from the shed and disposed well away from the packing shed. A single rotten fruit in the shed or receival area is a prime source of spores that can inoculate healthy fruit and the entire shed. It is also ideal to have a separate area for receivals of fruit from the orchard to the packing and re-packing lines. Good postharvest hygiene is key to managing resistance. In addition to fungicides, sanitisers should be used to wash and clean the fruit surface.

Optimise fungicide use

As described in Australian Citrus News Spring 2017 (pages 12-14), fungicides are classified into different groups depending on the way in which they work. It is important to understand the way each fungicide works in order to develop strategies to minimise the development of resistance.

In summary, TBZ is classified as Group 1, imazalil is Group 3, imazalil and pyrimthanil are Group 3 and 9, fludioxonil is Group 12 and guazatine is Group M7. To reduce the risk of fungicide resistance, it is important to limit the total number of fungicide applications from any one class, ideally to one per fruit lot. The continued use of the same fungicide class can cause selection pressures for that chemical, resulting in resistance.

Another important management practice to reduce the risk of resistance is to use rotations and mixtures or pre-mixtures whenever possible before resistance selection occurs. This makes it difficult for the fungus to develop resistance as there are different modes of action for each of the mixtures against the fungus. Strictly follow the specified label rate for each fungicide. Applying lower rates of fungicide can enable natural selection of less sensitive spores in the population.

Optimise fungicide efficacy

It is important not only to use the correct fungicide but to use it correctly, as fungicide coverage determines the efficacy of the treatment and minimises the chances of decay spores surviving following treatment. The use of sanitisers and alkaline salts in the packing line to kill pathogens is also a good way to reduce the risk of fungicide resistance. Sanitisers have a broad method of killing fungi and resistance to these chemicals is unlikely.

Monitor fungicide resistance

It is important to routinely monitor pathogen populations for their sensitivity to postharvest fungicides. The early detection of potential resistance issues increases the chance that its development can be managed and stopped. Routine hygiene monitoring can also help with knowing that your sanitation and cleaning programs are working.

More information

John Golding, NSW DPI: john.golding@dpi.nsw.gov.au or 02 4348 1926

Acknowledgement

The researchers thank the co-operating packing shed managers and growers for participating in the 2017 Hort Innovation CT15010 Packingshed Survey. Special thanks go to to Craig Wooldridge at E.E. Muir & Sons Pty Ltd for assisting with the collection of the plates for the survey in some sheds.

This is article is a contribution from the Australian Citrus Postharvest Science Program (CT15010) funded by Horticulture Innovation and the NSW Department of Primary Industries. Levies from Australian citrus growers are managed by Horticulture Innovation and contributed to funding this project. The Australian Government provides matched funding for all Horticulture Innovation research and development activities.

Membership

You are not logged in

If you are not already a member, please show your support and join Citrus Australia today. Collectively we can make big things happen.